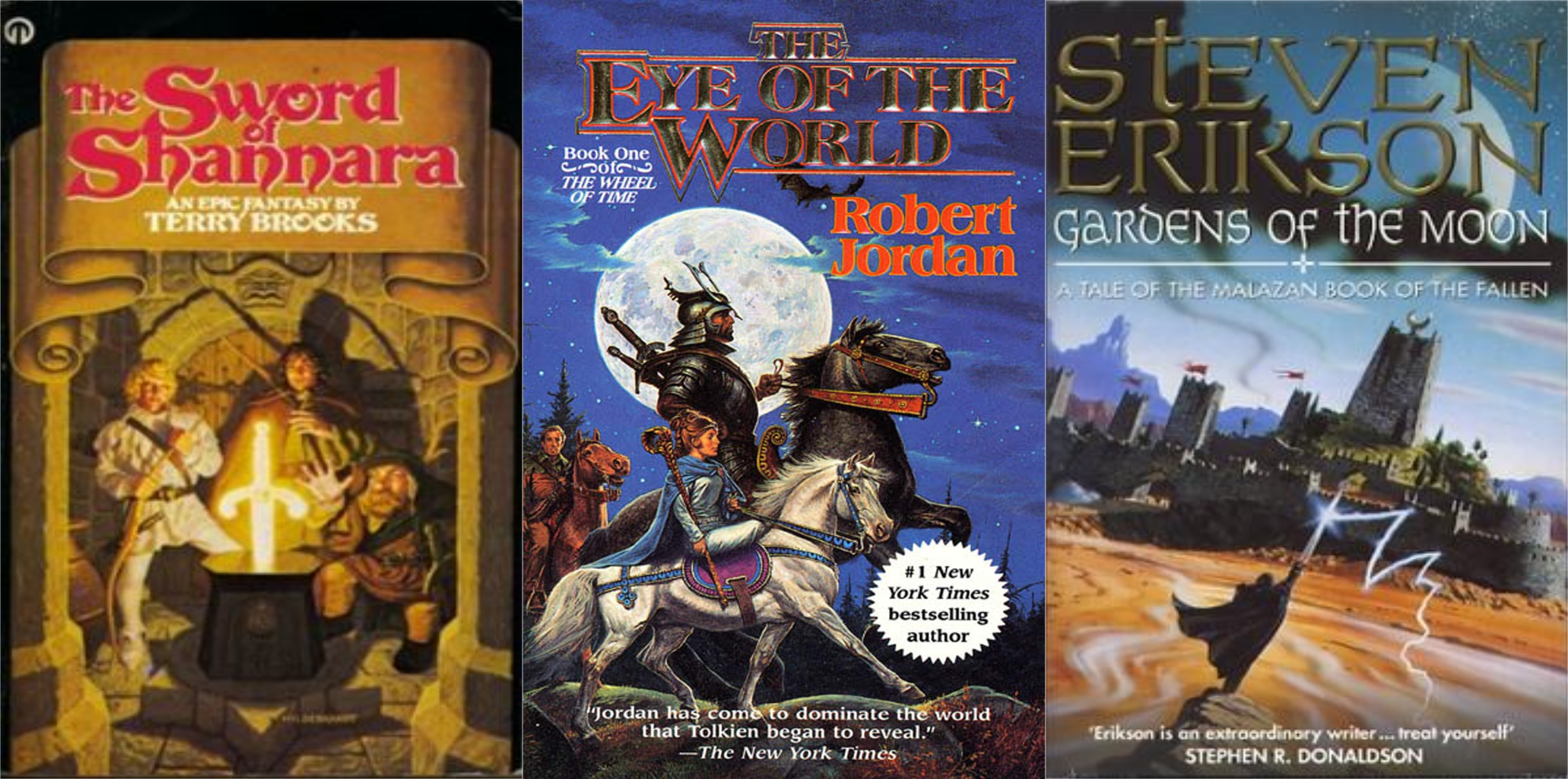

The idea of copying another is taboo and flattery at once. On the one hand, something has to be said for originality and the protection of intellectual property, while on the other hand a certain level of accomplishment and pride can be measured when something becomes the subject of imitation. While certain liberties can always be taken, it is a subject of heated debate when the line from imitation to forgery is crossed. Though perilous be the path from inspiration to imitation, we see that journey taken time and time again. It can be seen within popular music, television and movies, household goods, as well as literature. One such example that both borrowed heavily from a much-loved story while also re-imagining it for a new generation of readers is the much debated The Sword of Shannara by Terry Brooks. Love it or hate it, it’s hard to imagine the current state of fantasy literature, at least from within the United States, if Brooks’ work had not found its way to bookshelves.

Though likely not uniquely the whole of the evolution of publishing toward the end of the twentieth center, it is clear that Shannara helped put the fantasy genre back into mainstream consciousness and reignited, to some degree, the world’s passion for something more fantastical than mere everyday happenings and a desire to escape the vicissitudes of life. Brooks freely admits his use of Tolkien’s work as the foundation and structure for this work. From his use of character patterns, copies of the peoples and races, to following the story’s iconic structure, and on to the faceless evil that must be overcome, Brooks would be hard pressed to deny more than a little bit of inspiration drawn from the works of the father of Middle Earth. He would go on to follow that first novel with nearly three dozen others in the setting he first seeded in Sword which would span generations within that world, each one evolving further from the formula initially used to become examples of what Brooks could really accomplish in his own strength.

Perhaps it could be argued that the serial format used in Brooks’ Shannara works does not live up to the standards set by more classical, front to back, epic storytelling. Though, his use of legacy as a theme, his fleshing out of the struggle between science and magic, and his ability to write relatable, flawed characters are proof that his detractors aren’t the only group that remember his name and his works. And with the structure of series within series it is possible for readers of all caliber to have something they’ll enjoy without having to commit to thirty-plus works.

In the wake of this publishing awakening, another author – who would later go on to write another mimicry of Middle Earth which would become something else – was in the middle of helping the world experience the reimagined pulp of Conan. No name in the sword and sorcery branch of fantasy is likely more well known than Robert E. Howard’s Conan. Action, violence, darkness, and sorcery were no match for the titular barbarian born in the 1930s when pulp fiction drew the minds of young and old out of their daily routines and showed them worlds that could only exist in the imagination. Though the post-Howard Conan is an evolution between what sword and sorcery had been and what epic fantasy was becoming it is worth noting that before the turning of the Wheel that would be Robert Jordan’s magnum opus he was granted the opportunity to write a handful of novels including a movie adaptation for that transition. Jordan’s opportunity to write Conan came due to having written his first novel, Warriors of the Altaii, in just thirteen days. So he took the job and enjoyed it as practice for what would come later. What would come later, The Eye of the World in 1990, would be the beginning of a modern fantastical adventure that would not be completed until after Jordan’s untimely death after having finished the 11th of what was intended to be a twelve book epic.

Another shameless imitation, The Eye of the World was set up to intentionally evoke the feeling of the shire and the hero’s journey. But it all started with this one book. The imitation of the Shire, the tropes of the farm-boy leaving home, the fellowship broken and no one left as they were before the journey began (admittedly, not specifically Tolkien inventions). Here though, we see a divergence. While Brooks boldly imitated, Jordan was able to take the influence and subtly escape accusations of counterfeiting. Gone were the elves and dwarves, and probably most divergent of all was the presence of what Tolkien lacked most: female characters. Not just female characters being present in the story, but female characters getting entire plotlines, point of views dedicated to females, and most shocking of all, his use of gender dynamics in the setting especially tied to the use of magic. Though divergent, it still felt of Middle Earth, and from a publishing perspective, if Tolkien could be rebottled as he was in Brooks then the nineties would flow with epic goodness. What would come later was able to set its own tone and ensure that Jordan was more than a pulp-writing, copyist, but rather a man of epic vision with an ability to paint worlds and lives with words in painstaking fashion.The pattern, it would seem, was set such that, for any aspiring young author, in order to be able to write and have published what they could create, they first had to show the ability to write Tolkien-esque. This would present a decade long struggle for what would become the introduction to The Malazan Book of the Fallen.

While Jordan was busy working on his follow-up works to The Eye of the World, another soon to be epic literary figure was trying to sell a screenplay based in the imaginative world of a tabletop role-playing game with fantastical characters and settings in a military setting. When Canadian archaeologist and anthropologist Steven Erikson, then Steve Lundin, couldn’t draw enough interest in the screenplay, he decided to convert it to a novel, Gardens of the Moon. Unlike some of his contemporaries, Erikson wouldn’t just not emulate Tolkien, but he would intentionally write against the tropes setup in Tolkien-esque literature. Erikson’s influences weren’t cut from that cloth. He’s spent time with Glen Cook’s Black Company, which was born from the ashes of the American conflict in Vietnam, a far more muddied image of conflict than the first world war. He had followed Conan on exploits of blood and grandeur, and confesses his trip to Middle Earth came far too late in life for it to influence his authorial voice. However, it was a bridge too far for American publishers. Fantasy without all the beloved familiarness of Middle Earth and the hero’s journey. No one would buy it. Fantasy as a sub-genre of literature had become a one root tree. The breath and life of what came before and alongside Tolkien was lost to general academia. Erikson would have none of it, and almost ten years of effort landed him a book deal with a British publisher, and the rest, well, as they say, is history.

Gardens of the Moon would launch the shared world of the Malazan empire and the many lands and characters introduced therein. With novels still in the works and Erikson’s constant interactivity with his fan base, it’s clear to see now that fantasy literature can live outside the shadow of Tolkien. That’s not to take anything away from what Tolkien and his imitators have accomplished, they are remembered and revered for good reason. Gardens of the Moon, though, needs make no apologies for being a copy, nor be ashamed for being too other. The only shadow in the garden is one placed there in the minds of those who’ve forgotten that fantasy literature has roots, not simply a root.

CodeLes (editor: Jagarr)